|

|

The Twin Bee rides well on the

water and breaks fairly cleanly despite the four foot extension added

to the

hull aft of the cabin. Some pilots claim the Twin Bee operates

well

in three foot waves because of its rugged construction and STOL

capability.

|

The twenty four UC-1 Twin Bees made by STOL

Aircraft, Inc.during the 1980’s occupy a unique

place in aviation history. They were the last multi-engine flying boats

produced in the United States. Through a quirk of fate, mine, hull #23,

is the newest of the type still flying and, as

such, is a unique historical artifact. The FAA Aircraft Register lists

thirteen UC-1’s. NTSB accident reports show that three of these were

destroyed

in crashes. A correspondent tells me he has the engines off a fourth.

That

reduces the total to no more than nine. The Twin Bee indeed is indeed

an

endangered species.

This detail of the rearward

opening cockpit doors demonstrates the potential problem should one

accidentally come open during flight. The doors have three

latches each as well as an emergency warning light. Also visible

is the Twin Bee’s roomy five place cabin.

|

When Joseph Gigante

and his colleagues of United Consultants undertook to design andproduce a

multi-engine amphibious flying boat, they decided not to go through

rigors of obtaining a new type certificate, but rather to modify the

existing Republic RC-3. They removed the 215 horsepower Franklin pusher

engine, added two and a

half feet to each wingtip, spliced a four foot section into the

fuselage

just aft of the cockpit and put two 180 horsepower Lycoming fuel

injected

IO-360 engines with constant speed, full feathering Hartzell propellers

atop

the wings.

The result was funny

looking and had serious center of gravity problems. It still looks

funny. The center of gravity problems were solved by increasing the 75

gallon main fuel tank to 85 gallons and adding a 16 gallon fuel tank

near the tail to or from which fuel can

be transferred in flight to adjust the center of gravity.

How does it fly? Over the past half century, I’ve learned that

funny looking planes fly funny. That said, let’s go for a ride.

You can get into very

serious trouble just

by not properly securing the doors. The pilotand copilot doors

are trapezoids measuring three feet by three feet that open to the

rear. As if the fact that an opening door would swing back and slam

into the fuselage were not enough, an errant door will also swing into

the propeller arc

and send the plane out of control. There are two extra fasteners on

each

door, a red flashing light if the doors are not locked and a steady

yellow

light if they are. What me worry?

Directional control

on the ground is a challenge. The vertical stabilizer is a huge flat

thing sticking twelve feet into

the air. The tail wheel swivels. The brakes fade when they get hot. A

quartering tailwind while taxiing on a narrow taxiway has embarrassed

the best of

us. Directional control on takeoff and landing is simplified by a

locking

tailwheel. Fear not, should you forget to lock it, you’ll know within

seconds

of advancing the power. Land with it unlocked and you stand a good

chance

of producing a 3,000 pound lump of crumpled sheet aluminum.

The Twin Bee’s relatively wide,

flat bottom is reminiscent of the Consolidated boats of the late

1930’s. The landing gear merely rotates out of the way for water

operations with no accompanying decrease in drag. The tail wheel

rotates ninety degrees clockwise. The Twin Bee’s relatively wide,

flat bottom is reminiscent of the Consolidated boats of the late

1930’s. The landing gear merely rotates out of the way for water

operations with no accompanying decrease in drag. The tail wheel

rotates ninety degrees clockwise.

|

Takeoff is

short, three hundred and seventy-five feet on land; eleven seconds

off the water. Like all flying boats,

adding power causes

the left wingtip to go down. This is not particularly serious

with

Lakes or RC-3’s, but the multi-engine boats have a propeller out there

that can suffer serious spray damage if the pilot is not careful.

Unlike the over-powered Widgeons, nose oscillation during takeoff is

not

likely and easily arrested should it

happen. From land or water,

takeoff is quick and spectacular.

A light twin (two wing mounted reciprocating engines and weighing

less than 6,000 lbs.) is not required to maintain altitude on one

engine.

The book says a Twin Bee will climb at about 200 feet per minute at

gross

with one feathered. However, NTSB records show at least one

instance

where it couldn’t. If someone shows you an ATP gotten in a Twin

Bee and all the events were honestly done, you stand in the presence of

a person to whom Chuck Yeager would demur.

During trimmed, steady-state cruise, every once in a while the

Twin Bee will

make up its mind to go wandering off. It suffers from phugoid, or

long term, oscillation. Try as one might, you can’t trim it

out. This doesn’t hurt anything or present a danger. It’s

annoying. During a five hour flight there will be several

unexpected minor “attitude excursions.”

Landing is a piece of cake with the caveat, “Thou Shalt Not Get

Slow!” With no flaps, the entire wing stalls at the same

time. With flaps down, the tips stall first, but not by

much. If you’re slow with low power, the Twin Bee can suddenly

drop out from under you. If you hit too hard bulkheads collapse,

rivet lines rupture and the hull floods.

Hit nose hit first and the part of Bernoulli’s Law speaking to the

greatest

force being perpendicular to the greatest curvature comes into play and

over

you go. NTSB records tell of an accident in which a student

attempting

a no-flap landing came to grief. The feds don’t speculate.

However, my reading of the report suggests the plane stalled, dropped

and flipped.

Traveller IV at rest on the shore of Pleasant Lake in the

Adirondacks at the FAA’s annual Seaplane Safety Seminar on Pleasant

Lake near Speculator, New York. Traveller IV at rest on the shore of Pleasant Lake in the

Adirondacks at the FAA’s annual Seaplane Safety Seminar on Pleasant

Lake near Speculator, New York.

|

Amphibians were designed without a landing gear warning

horn. Being a longtime member of that majority of amphib pilots

who have landed gear-up on a runway, I ordered Lake and Air’s “Landing

Gear Position Announcing System.” Now, for less than $2,000

installed, I have a nearly fool-proof system.

Flying boats failed as airliners because loading and unloading on

the water is inconvenient. The wingtip float keeps you from

siding up to a dock. Nose-to docking requires a crew, spring

lines and bumpers. Loading and unloading from a lighter at a

mooring usually degenerates into a gymnastics exhibition. The

most convenient way to load and unload a flying boat is on solid

ground, and even that is not always graceful. If you

must fly a boat, you have to accept that loading and unloading is not a

single person activity, and it usually requires special equipment.

Despite its looks, nasty habits and glacier slow cruise, I love

owning and flying a piece of history.

Traveller IV’s

instrument showing all the bells and whistles including a three axis

autopilot and GPS that this onetime Part 135 bird is fitted with. Traveller IV’s

instrument showing all the bells and whistles including a three axis

autopilot and GPS that this onetime Part 135 bird is fitted with. |

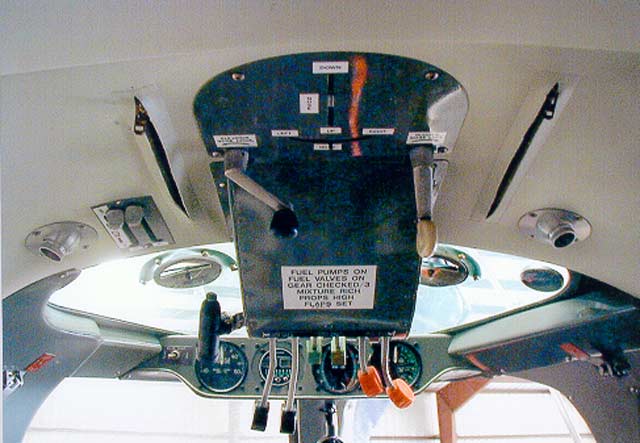

The overhead panel has the engine

controls, trim wheels and engine instruments. Reaching up to

change power settings seems a little strange to some when they first

start flying boats. In the foreground are the elevator and rudder

trim handles. Next is a panel light. The overhead panel has the engine

controls, trim wheels and engine instruments. Reaching up to

change power settings seems a little strange to some when they first

start flying boats. In the foreground are the elevator and rudder

trim handles. Next is a panel light. |

Traveller IV

beached. This shot typifies the difficulties with loading a

flying boat. If the surface is firm enough and there is enough

room, the flying boat can be taxied far enough onto the beach to allow

boarding from dry land.

|

If the surface is

firm enough, the Twin Bee can be taxied far enough onto the beach to

allow passengers and freight to be loaded

on dry land. If not, you will get your feet wet. This shot

also show the advantage a flying boat with conventional gear has over a

flying boat with tricycle gear or a float plane when leaving the plane

“beached” over night. If the surface is

firm enough, the Twin Bee can be taxied far enough onto the beach to

allow passengers and freight to be loaded

on dry land. If not, you will get your feet wet. This shot

also show the advantage a flying boat with conventional gear has over a

flying boat with tricycle gear or a float plane when leaving the plane

“beached” over night.

|

A deserted beach

after the FAA’s safety seminar at Camp of the Woods on Pleasant Lake

near Speculator, NY. An amphibious flying boat, such as the Twin Bee,

has the advantages of being able to operate from a hard surface, a

remote lake

and in the IFR airways system. A deserted beach

after the FAA’s safety seminar at Camp of the Woods on Pleasant Lake

near Speculator, NY. An amphibious flying boat, such as the Twin Bee,

has the advantages of being able to operate from a hard surface, a

remote lake

and in the IFR airways system.

|

Traveller IV on take

off on the Connecticut River near the Goodspeed Seaplane Base. The

plane is just rising on the step. Shortly, the pilot will correct

the left wing low condition characteristic of a flying boat at this

stage of acceleration, and complete take off. Traveller IV on take

off on the Connecticut River near the Goodspeed Seaplane Base. The

plane is just rising on the step. Shortly, the pilot will correct

the left wing low condition characteristic of a flying boat at this

stage of acceleration, and complete take off.

|

|