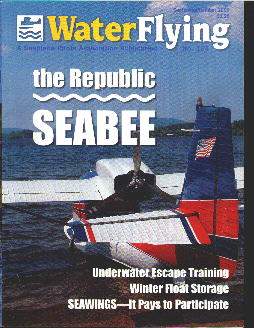

The Republic

SEABEE: A Plane for All Occasions

The Republic

SEABEE: A Plane for All OccasionsBy Jim Poel

"I was introduced to the Seabee in

1970 when Chuck Bassett (SPA #1750)

took me flying in his Seabee. Chuck, who is a retired captain for Pan

Am, used to fly both the Sikorsky and Boeing Clippers. I was impressed

that someone with his credentials was so enthusiastic about Seabees.

Even though I thoroughly enjoyed the flight and wanted one of my own,

it was to be almost twenty years before I was to become the proud owner

of one."

|

We owned a Piper J-3 on straight floats for a while. Although a

lot of fun to fly, I didn't like having to leave it out in the weather

by

a lake - especially since we lived in an airpark with a hangar right in

the backyard. We knew we loved water flying and antique airplanes. And

we

wanted four seats so we could share the fun with others. The Seabee

seemed like just the thing. It had everything we wanted, plus (although

not a speed demon), it cruised almost one-third faster than the J-3.

I spotted my pretty blue Seabee at the Daytona Beach

International Airport. The tires were flat from being immobile for a

number of years. However, it looked basically good, so I called the

owner and soon a deal was struck. After some work, we got it running

and I was able to ferry it the five miles to our airpark.

Once the airplane was in the hangar, I started learning a lot

about Seabees. I read all the manuals, service bulletins and numerous

other publications. All of them were smudged with many greasy

fingerprints as testimony of

their use. The manuals are not only easy to read, but fun having

expressions

like, "tighten to a moderate pinch". or "using a four-foot bar, tighten

with the strength of an average man."

I found that my restoration proceeded in stages. First I'd fix

something, fly it, fix it again, fly it, and finally, fix it the right

way. I can

still remember the first time I flew my new Bee, when everything worked

great!

Seabee History

The basic design of the Seabee is, in a word, simplicity. Based

on the design of Percival H. Spencer's Aircar, the Seabee has less than

five hundred parts which is a fraction of the two-thousand-plus parts

in most production aircraft. The Seabee was Republic's answer to the

post war, civillian market-a family plane that could go anywhere. At an

initial price of $3995, over one thousand were built in 1946 and 1947

before the production line was shut down. There are approximately

200-300 Seabees still registered with the FAA today.

The Engine

The original engine, the "Franklin 500" was built by Air-Cooled

Motors in Syracuse, New York. It is a

500-cubic-inch, 215 horsepower engine that converts 80-octane avgas to

noise and thrust at the rate of 14 -18 gph. There is a twenty-six inch

prop shaft extension that allows the engine to be positioned forward

for better balance. Although some owners have converted to larger

horsepower geared Lycoming engines, most Seabees are still powered by

Franklin engines.

The Prop

Seabees are approved for two or three blade, variable pitch,

hydraulically actuated (did I mention reversible?) propellers.

Originally this was a two-blade Micarta prop.

Airfoil and Cabin  A Seabee's lift is

generated by the Clark Y airfoil of the huge

thirty-nine foot wing and engine cowling, also the famous Clark Y

shape.

The flight controls are of basic cable and pulley design operated by

the

control wheel. Overhead is the pitch trim crank handle and just to th

left

of it is the fore and aft sliding reverse lever with a lock in the

forward

position. A Seabee's lift is

generated by the Clark Y airfoil of the huge

thirty-nine foot wing and engine cowling, also the famous Clark Y

shape.

The flight controls are of basic cable and pulley design operated by

the

control wheel. Overhead is the pitch trim crank handle and just to th

left

of it is the fore and aft sliding reverse lever with a lock in the

forward

position.

Seabees have three doors: left side, right side, and a bow door.

The latter is used for egress at a dock (more on that later). The right

side control wheel can be removed by the pull of a pin and stowed in a

tube under the right side of the front seat. In the floor under the

copilot's feet

is a hatch in which the 5-pound Danforth anchor resides. The front

seats are

adjustable fore and aft and recline fully to make a bed. The rear seat

is

not only roomy, but is located ahead of the wing. This offers

phenominal visibility

for the rear seat passengers. Behind the rear cabin bulkhead is the spacious cargo

compartment that can hold up to 200 pounds. Fuel is stored in one

seventy-five gallon bladder tank located under the cargo compartment

and is protected by a double hull. There is an official size and weight

dipstick marked in five gallon increments for measuring the amount of

fuel on board. There are five watertight compartments, each with its

own drain in the keel and pump out tube in

the side of the fuselage. In addition to the standard red, green, and

white

navigation lights, the Seabee also has a small white anchor light at

the

top of the tail. This is used in conjuction with the reclining seats

when

anchoring out overnight.

Gear and Flaps

The gear and flaps are hydraulically actuated using selectors

and a hand pump in the center of the floor, just forward of the front

seat. Some owners have added hydraulic pumps to lessen pilot workload.

Each flap is totally independent so it is possible to have one flap up

and one down, but this is not a problem as there is enough aileron

control to override this condition. Once again, simplicity. Each main

landing gear is held onby two large bolts. These, along with a snap

fitting in the brake line can be

removed in a few minutes rendering a straight seaplane that is one

hundred and fifty pounds lighter. The original taiwheel was a castering

full-swivel locking type. Later an option was available for a steerable

one.

Aircraft Handling  Learning to fly a Seabee is no major feat for anyone who is

proficient in complex and tailwheel airplanes. The old adage applies

here as with any other conventional gear airplane-once the tailwheel

gets outside the main gear, everyone in the plane becomes a passenger.

With the engine mounted on the same level as the wing and pointed

directly into the tail, there

are no pitch variations resulting from power changes. Also, being a

pusher,

the prop is very close to the aft control surfaces. A good blast of

power

adds immediate elevator and rudder control. I would like to add here

that

the elevator trim tabs are very large. This makes the trim very strong

and cannot be overridden by control-wheel pressure. The aircraft can,

however, be flown using only trim for pitch control. In general,

handling is somewhat heavy but very stable.

Learning to fly a Seabee is no major feat for anyone who is

proficient in complex and tailwheel airplanes. The old adage applies

here as with any other conventional gear airplane-once the tailwheel

gets outside the main gear, everyone in the plane becomes a passenger.

With the engine mounted on the same level as the wing and pointed

directly into the tail, there

are no pitch variations resulting from power changes. Also, being a

pusher,

the prop is very close to the aft control surfaces. A good blast of

power

adds immediate elevator and rudder control. I would like to add here

that

the elevator trim tabs are very large. This makes the trim very strong

and cannot be overridden by control-wheel pressure. The aircraft can,

however, be flown using only trim for pitch control. In general,

handling is somewhat heavy but very stable.

The biggest challenge is taxiing in a strong crosswind. The

massive tail wants to weathervane, so you add lots of power while

holding full downwind rudder and brake pressure. Remember, I said a

good blast of power gives rudder and elevator control? Well, about this

time, just as you think you have the right combination, if you are not

holding a lot of back pressure on the control wheel, the tail can lift

until the keel under the bow touches the ground. Although this maneuver

doesn't hurt anything, I still haven't figured out if it appears

sillier from inside or outside of the aircraft.

Takeoff and Cruise

Because the engine is in the middle of the aircraft and the

passengers are in the front, the procedure used to set the trim for

take off is somewhat different than most other airplanes. The pilot

firast cranks the trim handle to the full nose down position, then

cranks nose up one turn for each

person aboard. Takeoff from land is fairly straightforward and can be

done with flaps up (for best climb), full down (for shortest roll) or

anywhere

in between. I prefer half flaps as it is a good combination of both.

The

book says the minimum ground roll is nine hundred feet. This is

accurate

using a short field technique. With half flaps and a heavy load, I

generally

have a ground run of 1200-1500 feet. Liftoff is at 65 mph. Once

airborne,

establish a climb speed of 80 mph, set climb power, select flaps and

gear

up andstart pumping. The flaps will come up but the gear must be

pumped.

About twenty-two strokes will do the job. The gear pivots up and stays

in the slipstream, so there is no aerodynamic benefit. The Seabee

shines

when lifting a load off the land or water, but climbing is in the

mediocre

category. While the book gives an initial climb rate of 700 fpm, my

experience

is more like 400-500 fpm. A cruise speed of 103 mph at 24 inches of

manifold

pressure and 2300 rpm is normal. This is 65% power and yields a fuel

burn

of 14-16 gph. Although the service ceiling is 12,000 feet, most

cruising

is done at altitudes below seven thousand feet.

Takeoffs from water are done with full flaps. I like to hold the

wheel full aft when power is applied. Very quickly, after the nose

rises, I hold full forward pressure which lifts the tail up, putting

the aircarft on the step. Lift off at about 60 mph. When accelerating

through 75 mph and at or above 200 feet, retract the flaps and climb

out at 80 mph. Once at 80 mph, the high lift wing allows bank angles of

30 degrees with no problem. This helps to stay over the water in a

tight area.

Seabees are known for their outstanding rough-water handling capabilities. At the risk of starting a "can you top this" discussion, I have talked to Seabee pilots who have taken off in two to three-foot waves. I have personally landed and taken off in eighten to twenty inch waves. While the airplane did just fine, I spent the next two days looking for my fillings on the cabin floor. One-foot waves are considered "Seabee chop". Approaches Approaches to land and water are identical except for the gear position. Full flaps are used for both. An approach speed of 80 mph is held until the flare, then hold it off until 65 mph and let it settle on. On land, if the aircraft is held off to a full stall, the tailwheel will touch first followed by the mains coming down with a thump. On water if youtouch down faster than 65 mph, it causes the aircraft to skip slightly as if the water were rejecting you until you get your airspeed under control. The deep "V" hull not only makes water landings very smooth, but also allows operation in rougher conditions than most other seaplanes. Floatplane pilots will notice that ailerons are still needed from after touchdown right up into displacement to keep the aircraft level. In displacement the water level is, depending on weight, about six to eight inches below the cabin floor, allowing all the doors to be open. Taxiing Water taxiing a Seabee is a true delight. You can bank into step turns for a fairly tight circle. With the reversing propeller, maneuvering is easy. Moving forward, backward or standing still is just a matter of adjusting the reverse knob on the ceiling. A cooling fan on the front of the engine provides airflow for engine cooling during these low speed operations. Docking Docking is done, as usual, from downwind, but the aircraft can be crabbed into a tight spot from the side. With the bow door open, and a boat cushion hanging on the bow cleat, the aircraft can slowly be eased up to a dock, using various degrees of forward and reverse thrust. Once contact is made, a little forward thrust will hold it in place and the rudder will allow directional control while passengers enter or exit. There is even a step just in front of the co-pilot's rudder pedals for this purpose. When leaving, just back away from the dock until there is room to turn. If there is a wide enough boat ramp ona beach, the gear can be extended and the aircraft taxied up to dry land. Beaching Beaching a Seabee is great fun! Once in displacement, pump the gear down and release the tailwheel lock, if so equipped. Then, proceeding slowly, taxi towards the beach or ramp until the wheels touch bottom. This is where the conventional gear and large tires are a real asset, as soft sandy bottoms and even small rocks are dealt with easily. As the weight is transferred to the wheels, slightly more power is needed. If the slope is steep, just taxi up at an angle to the beach. Ince high and dry, point the nose towards the water for easy downhill exit, shut down, and break out the picnic or camping supplies. Safety Issues As with any amphibian, landing with the wheels down on water creates probably the biggest hazzard. Installing a Gear Advisory System in your Bee is an excellent investment in safety. The reverse, landing with the wheels up on land (though not recommended) does little damage as long as the wings are kept level. Among the Seabee crowd, this is known as "sharpening the keel". The temptation to fill the cavernous interior can lead to overloading the aircraft. The Seabee must be loaded carefully to avoid CG problems. There is a placard next to the fuel filler that requires a five-minute span between engine shutdown and measuring the fuel with a dipstick. It seems that the fuel return line that drains from the engine, drips right onto the forty-five-gallon mark of the dipstick. The safest technique for fuel measuring is to wait the required five minutes, then insert the stick with the numbers facing down. Although needing lots of TLC and a great deal of understanding (as do any of us who are over fifty years old), the Seabee is still going strong. The rugged construction, unique simplistic design and excellent corrosion proofing allow it to continue to give many hours of enjoyment. The Seabee is not only a true antique classic- it is a plane for all occasions. Water Flying Magazine - September/October 2000 |